By Jim Martin

<back to top>

Fitness & Training for Bicyclists

These articles appeared in Bicyclist Magazine (previously, Bicycle Guide), which has since gone out of business and reappeared as Bike, a magazine dedicated to mountain bicycling. I have captured and re-produced these articles here to ensure that they are not lost from the web.

An Athlete's Primer for Defining the

Term

An Athlete's Primer for Defining the

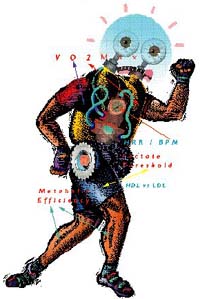

TermEverywhere you look these days, the topic is fitness: how to get fit in 10 minutes, how to be fit for life, how to be fit not fat. Infomercials on late-night TV proclaim that you can be fit if you buy their latest fitness gizmo for only $49.95. Superbeef gym or Barbie's fitness center will get you fit for the beach for only $39 per month. Weight lifters think of themselves as fit, as do aerobics instructors and football players, and certainly we as cyclists think we're very fit. With all these differences, it's no wonder most of us have only a vague idea of the meaning of a word we use almost every day. Even those supposedly in the know have different ways of describing fitness. Many coaches think in terms of percent of maximum heart rate, whereas most physiologists think in terms of percent of VO2 max. Over the next year, this "Training" column will feature articles on various types of training that will target specific aspects of fitness. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to explain the physiological and metabolic components of fitness that are important for cycling and define a common language which we will use over the coming year.

Fitness for the endurance cyclist can be divided into four general categories:

This is usually defined as the maximum rate at which you can take in and use oxygen (VO2 max: the maximum volume flow rate of oxygen) and is determined by measuring the amount of oxygen that you extract from the air you breath during maximal exercise. The protocol is usually a fairly short (6- to 10-minute) test on a cycle ergometer during which the workload is increased until you fail, and you will fail. Results are expressed as either absolute VO2 max (liters/minute) or relative to body weight (milliliters/kilogram/minute). Absolute values range from around 2.5 l/min. in smaller people to over 6 l/min. in elite men and from about 40 ml/kg/min. to over 80 ml/kg/min. when expressed relative to body weight. When cycling over flat terrain, absolute VO2 rules. However, if the road points upward, relative VO2 max will become more critical.

What determines VO2 max? It is primarily limited by the amount of oxygenated blood the cardiopulmonary system can provide to the working muscles and, to a lesser extent, by the amount of oxygen the working muscles can extract from the blood. The delivery of oxygenated blood to the working muscles is limited by cardiac output, which is the product of heart rate and stroke volume. The ability of the working muscles to extract oxygen is characterized by the arterial-venous oxygen difference (a-v O2 difference). The exchange of oxygen at the lungs is probably not a limiting factor in normal, healthy people at low altitude, but may be limiting in highly elite endurance athletes or in normal people at high altitude. The main benefit of training is to increase stroke volume. Although maximum heart rate is thought to be unaffected by training and to decrease with age, some studies have found that training helps maintain maximum heart rate during aging.

This is a measure of how well you have trained your working muscles. Most everyone, except the most highly trained, is limited by metabolic rather than cardiovascular fitness. You will know when you have attained really high metabolic fitness because you become what is called "centrally limited." That is, you will be able to ride at heart rates very near maximum without your legs screaming. Really, it happens! The best indicator of metabolic fitness is probably your lactate threshold (LT), which is often inaccurately called anaerobic threshold. (Briefly, the term anaerobic threshold implies that the muscle is operating without oxygen-however, the accumulation of lactic acid in the blood at submaximal intensities is a normal part of aerobic metabolism.) LT is determined by the amount of muscle mass you recruit (i.e., how well you distribute work among muscle fibers) and by the capillary density and mitochondrial density of that muscle. The capillaries are the smallest blood vessels in the muscle and are the place where oxygen exchange occurs; when these are increased in number with training, oxygen transport occurs more readily. The mitochondria are the aerobic powerhouses in the muscle-these too increase with training and are perhaps the most important element of metabolic fitness. They metabolize fat and glucose together with oxygen to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy currency of the muscle. LT is measured by taking blood samples during several submaximal work rates on a laboratory ergometer. The characteristics of the work rate versus lactate relationship are these:

1. At low work rates, the lactic acid level in the blood remains about the same as resting levels. This level is referred to as baseline. The lactate level remains low because the rate at which lactate is produced by your muscles and cleared from the blood are about equal.

2. As the work rate is increased, lactate levels in the blood increase, and at some point the lactate concentration exceeds a limit (various labs use different criteria) which is defined as lactate threshold. An untrained person will reach lactate threshold at about 50 to 60 percent of his VO2 max, whereas a well-trained cyclist will reach LT at about 75 to 80 percent of his VO2 max.

3. At intensities above LT, the lactate versus work-rate curve becomes very steep, indicating that lactic acid and other metabolites are accumulating in both blood and the muscles.

There is another side to metabolic fitness: metabolic efficiency (ME). ME is determined in a protocol similar to the one used to determine LT. From the measured gases (e.g., inspired and expired O2 and CO2), the amount of metabolic energy you are producing can be calculated. Since the amount of work you are performing is known, it is easy to determine the portion of metabolic energy that produces mechanical work and the proportion that produces heat. Metabolic efficiency can vary from 20 to 25 percent and is highly dependent on the percentage of slow-twitch fibers in your muscles. This range may not sound like much, but think about it: For roughly the same VO2, an inefficient rider may produce, say, 200 watts while a very efficient rider will produce 240 watts-a power difference of 20 percent! Unfortunately, there may not be much you can do to improve your ME other than change your fiber type. Although it is possible to change muscle-fiber type by chronic nerve stimulation, this has never been proved to occur with training. Anecdotally, we observe that elite cyclists who have trained for many years have a high proportion of slow-twitch fibers, but it is not known for sure if the training caused the observed distribution or if they became elite because they had the efficient fiber type to start with.

The best predictor of endurance performance is the power you can produce at your LT. This is a great composite measure because it takes into account your VO2 max, your LT and your ME. However, even power at LT is not a limiting value for endurance performance. Most people can perform for one hour at 10 to 15 percent above their LT. Elite cyclists with LTs of 80-plus percent have ridden for one hour at 93 percent of their VO2 max, and less trained cyclists with LTs of about 70 percent can maintain about 80 to 85 percent.

Muscular fitness is hard to define, but it usually involves some measure of maximal power output. In a lab we might measure your peak power, which might range from 600 to 2000 watts for about three seconds. Or, if you really wanted the bottom line, we could give you a 30-second all-out Wingate test, during which you would briefly (5 to 10 seconds) produce your maximum power, then fatigue for the last 20 to 25 seconds (Ouch!). Muscular fitness is related more to your ability to recruit muscle mass (which can be developed through strength-training techniques), and even though you may not consider yourself a sprinter or power athlete, if you ride a bike, you are a power athlete.

When people talk about fitness, there is often confusion in terminology. People often use percent of maximum heart rate when they mean percent of VO2 max and vice versa. While there are many problems related to quantifying intensity when using a heart-rate monitor, it can give you some meaningful feedback and you may be able to make some general guesses based on a calculation of heart-rate reserve (HRR). The first step in this calculation is to determine your max heart rate (best to have this done in a lab with medical care available). Secondly, you should determine your "no load" heart rate. To do this, just put your bike on a trainer with no resistance and pedal at about 30 rpm. This no-load heart rate is probably better than resting heart rate for determining HRR. Now let's say your max was 190 beats per minute (bpm) and your no-load was 90 bpm. This gives you an HRR of 100 bpm. The percent of HRR is roughly (and I mean roughly) equivalent to percent of VO2 max. You can calculate the percent HRR as: percent HRR = 100 x no-load HR/HRR.

For instance, if you did a flat time trial and kept your heart rate at 170 bpm, you could calculate that you were at 89 percent of HRR [100 x (170-90)/100 = 100 x 80/90 = 89 percent]. This would indicate that you were at roughly 88 to 90 percent of VO2 max, indicating that you are very fit!

What about good, old health? As a cyclist interested in fitness, you probably are most concerned about how far or fast you can ride your bike. Also, as a person interested in health, you are probably interested in your weight, blood pressure and your potential to develop heart disease or diabetes. Coincidentally, everything you do to improve your cycling fitness will also improve your health. Training increases the good HDL cholesterol in the blood and decreases the bad LDL. After exercise, your muscles take up blood glucose more rapidly. Exercise decreases blood pressure. Training also raises your resting metabolic rate so you not only burn calories while you ride, but you burn more during the rest of the day. Both your fitness and your health benefit from endurance cycling training. So, next time you feel torn between fitness and duty, go ride--think of it as preventative medicine.

Jim Martin was the 1988 Master's 30- to 34-year-old National Match Sprint Champion. Currently, Jim is the coach and director of sports science for Team EDS and is a doctoral candidate in kinesiology at the University of Texas. Additionally, Jim has served as a technical consultant to Project '96 on cycling aerodynamics.

Strength Training: Weights Now

Equals Power Later

By Jim

Martin

<back to

top>

What a great feeling: You're sitting comfortably in the lead group with only a few miles to go. You made it through the hills with the best climbers, and now finally, finally, you're going to finish in the front group. Then you hear it over your left shoulder-the whoop-whoop-whoop of tires under power. You turn to see a rider out of the saddle launching an all-out attack. Immediately, the bunch reacts and goes single file. You're pushing as hard as you can, but you find yourself going backward. Rider after rider goes around you and suddenly, inexplicably, you find yourself off the back. Darn! Not again! Why, if you're fit enough for the climbs, could you not handle the attack?

Sound familiar? It should. Almost every rider I know has gone through a phase in which he has the fitness to race or ride fast group rides but he lacks the speed to handle the serious attacks and the sprint finish. Mass-start bicycle racing places physiological demands on you for both aerobic endurance and anaerobic power-demands that are somewhat unique in the athletic world and not fully compatible with each other.

With endurance training, you make various adaptations to your cardiovascular system and to your muscles that allow you to ride at high levels of effort for several hours. You also make adaptations in the way your central nervous system (CNS) recruits your muscles. Specifically, when you train for endurance, your muscles' motor units are recruited asynchronously. That is, you recruit only a portion of your muscle fibers for any given pedal stroke. This is great for endurance, where the demand for muscular power is low, but it is disastrous for those brief periods when you need maximal power. For instance, it is common for endurance athletes to see dramatic increases in their vertical jump after they stop training. To gain power, your CNS must be reprogrammed to fire all your muscle fibers at once. One of the best ways to teach your body to recruit all your fibers for maximum power is with good old-fashioned strength training. With winter upon us, this is just the right time to head for the gym and begin to build a strength base for the attacks that will surely come fast and furious next spring.

Cycling is a sport of hip and knee extensions-therefore, the lifts you perform should mimic these actions. The primary lifts are squats, dead lifts, knee extensions and hamstring curls. If you don't feel comfortable with free-weight squats and dead lifts, the squat machines or sleds common in gyms are good alternatives. Calf raises are also valuable, but in my opinion, the only safe calf-raise machine is the "donkey calf," or the sled. Cycling requires minimal upper-body strength, but biceps curls and bench presses or, better yet, decline bench presses provide some balance for your chest and arms.

Step 1: First, you need to find a gym where you're comfortable. Gyms run the gamut from a few free weights in a small space to the chrome and glass at the singles gyms, so spend a little time and find one that's right for you. Most gyms will give you a trial pass for one workout, so try two or three before you plunk down your cash.

Step 2: The first day you lift, keep the weights and repetitions low. For instance, even though you may have squatted eight reps of 225 pounds last spring, you should start with no more than, say, four reps of 85 pounds for your first time out in the fall. If this is your first time lifting, be very conservative. I recommend on the first day you simply lift the bar a few reps and leave.

Here are two pointers for the first few days in the gym: 1) Don't let someone take you through a fitness evaluation where you do maximum lifts at every station. This will leave you so sore you probably will not walk well for three days. 2) Remember you're in the gym to become a faster cyclist. It's easy to get distracted from this point when you see all the he-man body builders walking around and you're looking at your skinny build in the mirror. Just remember: You can drop those guys like a stone. Plus, they're not even athletes-they're posers, literally.

Step 3: During these first few visits to the gym, while the weight is light, you want to learn the proper technique for each lift. Be careful to keep all your movements slow and controlled. Always lift with a spotter present (many gyms will provide someone for you.)

For squats, the most common mistake I've seen is to position the bar too high. Often I see people with the bar right on their necks. This can lead to serious injury. The correct position for the bar is about the upper third of your shoulder blades. This will be uncomfortable for your arms at first, but it will save your neck and give you better balance with heavier weight you will lift later. Position your feet about shoulder width apart, with your toes pointing straight ahead. Keep your back flat and squat down until your hamstrings are about parallel with the floor. This is called "bottom parallel" and is as far as you need to go for roaf riding training. Learn to stray balanced and keep your heels on the floor. Many people use a board under their heels while squatting because they don't gell comfortable or balanced with their feet flat on the floor, but I do not recommend it. I suggest you tru to adjust to lifting with your feet on the floor by staying conservative with the weights and gaining flexibility.

Straight-legged dead lifts are performed with the knees slightly bent and are an exercise in simple hip extension. Grip the bar with a reverse grip, one hand palm out and one palm toward you. Use a dead-lift platform so you can take the bar down to your shoe tops. Lift the bar until your torso is slightly less than vertical. The habit you will see at the gym of leaning way back with the wright is pointless and potentially injurious.

For knee extensions and hamstring curls, take care to position the center of your knee at the center of rotations of the machine's arm.

Step 4: After three to four workouts of learning the lifts and getting over any initial soreness, you are ready to start strength training. I recommend onlyu lifting twice a week, with at least two days of recovery. Mondays and Thursdays work best for me, but you'll have to devide what works best with your schedule. Here is a general guidelin for a four-month lifting program, beginning after the initial period previously described.

Weeks 1 to 4: Keep the weights light enough so that you can handle two or three sets of 12 to 15 repetitions. This period is aimed at learning the lifts, gaining flexibility and preventing injury. As you get stronger, increase the weight so you are at or near failure at the last rep.

Weeks 5 to 8: Increase the weight so you can only perform three sets of 8 to 10 reps at each station. Alternate the number of reps you perform in your two workouts (e.g. Monday is a 8-rep day and Thursday is a 10-rep day). As before, increase the weight so as to elicit failure on the last rep of the last set.

Weeks 9 to 12: Decrease the reps again, this time to three sets of six to eight reps. By now, the weight is starting to get pretty heavy, and you'll have gained a lot of confidence in the gym and in your strength. Increase the weight as needed to elicit failure.

Weeks 12 to 16: Continue to perform six to eight reps but only two sets. Decrease the weight by about 20 percent and increase the speed of each lift. Do not jerk the weight, but lift it quickly during the extension phase. This explosive type of lifting will prepare you for the maximum acceleration you'll need on the bike.

Weight training can provide a nice break from on-the-bike training and give you more speed when you need it. Always keep in mind that you're lifting to become a better cyclist, not a body builder. Remember this when the person next to you is lifting three times as much as you. Hang on to your self-esteem and don't try to compete in the gym, as that is the quickest way to get injured. Be conservative and stay healthy, and you will find yourself riding with newfound power and speed in the spring. Be strong and you will fear no attack!

Tireless Legs Part One:

Base Miles

By Jim Martin

<back to

top>

When I was a kid, comic

books featured ads for some sort of body building program. This was the real

thing, in which the skinny guy gets sand kicked in his face, then gets all

muscled up and finally whips the bully and gets the girl. In one panel, the

newly muscled guy is shown striding along the beach, admired by bikini-clad

women, and the caption claims that following the program will give you "tireless

legs." Tireless legs-wouldn't that be great? Thirty years later that phrase

still sticks with me.

All of us have been beginners or have simply taken a hiatus from training at one time or another. You know what it's like: You can ride along at an easy pace, but the instant you try to pound the pedals, your legs just seize. It happens before your heart rate or breathing goes up, and it's frustrating and embarrassing. Your friends have to wait up for you-it's awful. It's roughly the same as having sand kicked in your face. So, like the guy in the ad, it makes you want to train for tireless legs. So what does it mean in a cycling context? Is it a realistic goal and, if so, how do you get there?

From the last training article you may recall that one of the limiting components of fitness is lactate threshold (LT). LT is a measure of the exercise intensity at which you produce lactic acid more quickly than your body can clear it. When you have a high LT (an elite rider will have an LT at around 80 percent of VO2 max), you become "centrally limited," that is, you can pound the pedals till you're breathing like a freight train and your heart rate is through the roof, but your legs aren't screaming. That's right, high LT means tireless legs.

LT is related to both the density of the muscle's capillary bed and mitochondrial enzymes. By having more capillaries per unit cross-sectional area in the muscle, the muscle cells are better able to breathe: Oxygen has a shorter diffusion distance from capillary to muscle cell, and metabolic by-products (including lactic acid) have a shorter diffusion distance out of the muscle. The increase in capillary density may be the main physiological adaptation that you achieve during your base miles. This adaptation does not come to complete fruition during one season; rather, it is an ongoing process that takes years. You will increase mitochondrial density, too, but probably not to the same extent (that will come later, during the power phase).

Base miles is a phrase that almost every cyclist uses, but it may not mean the same thing to everyone. In general, I would describe base miles in the following terms:

When you ride at low intensity, you recruit primarily your small, slow-twitch motor units (a motor unit is a combination of a single motor neuron and the muscle fibers which it enervates). These slow-twitch fibers are, by nature, well trained. That is, they have relatively high capillary and mitochondrial density. When you increase the intensity, you recruit the larger, fast-twitch motor units, which have less aerobic capacity. It is these motor units that you really need to train in order to raise your LT and avoid that God-awful leg seizure when you stomp on the pedals. Clearly, the most obvious way to recruit and train these fast-twitch fibers is to increase intensity. But, as you have already experienced, that causes rather abrupt fatigue. Another way to recruit the fast-twitch fibers is to ride long enough so the slow-twitch fibers become fatigued, primarily due to glycogen depletion. In this way, the fast-twitch fibers are recruited very gradually and you don't experience the sudden accumulation of lactate (sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, etc.). Instead, you experience a feeling of emptiness in your legs that is, well, sort of satisfying.

For me, the thought of base miles evokes fond memories of rolling through a brown central Texas winter landscape with a fairly big group, always in a two-by-two line. These are times of story telling, lying, bragging and general bikie bonding. You'll take long pulls, maybe five minutes, but they will be fairly slow. Of course, the intensity in the draft is even lower. The low intensity makes it easy to carry on conversations. Furthermore, by riding slowly you can get comfortable and relaxed riding close to one another. This is a skill that is difficult (and dangerous) to develop under the pressure of high-speed racing or group tours. Base rides in a group serve as both training and practice sessions and provide a great time for the telling of tall tales.

If you follow up a long base ride with another the next morning, chances are you will not be completely recovered from the first ride. This is a good thing, and something you can make use of. In a single ride, you fatigue the easily recruited slow-twitch fibers and then get down to the real business of recruiting and training the fast-twitch fibers. By riding again before you are fully recovered, you extend the process into the second ride. So if you start that Sunday ride feeling stiff and weak, rejoice, you're getting maximum benefit. Of course, you don't want to take this any further than two days, so you'll want to have a rest or strength-training day on Monday (surprisingly, even when you're very tired you can still lift just fine). Also, you'll want to really eat well after these rides to speed recovery for the coming week.

If you put in base miles during the winter and early spring, your endurance will increase dramatically. You'll find that the two-hour ride that initially wore you out now just makes you feel good; that is, for low speed, you will have earned tireless legs. This, by itself, is a great result for many riders. Some of you, however, have your sights set on going longer and faster. You will find that this base work sets the stage for you to start working on aerobic power. If you've never trained systematically for a whole year, you will be really surprised to see how quickly you progress when you start your power work. Physiologically speaking, these base miles have increased your capillary density and somewhat increased mitochondrial enzymes. This has the effect that when you start riding at higher intensities, the metabolic by-products more readily diffuse out of the muscle. You will find yourself riding at higher and higher heart rates without the sensation that your legs are stuffed (a term used by British track riders that is wonderfully descriptive of when the legs have had it).

So for now, try to establish a habit of putting in easy group rides for the next several weeks. Call around and find a group ride that you can depend on and that you like. One tip when looking for a ride: the better the riders the more polite the ride. Don't be intimidated by the local elite riders because they will often be a better group for winter rides than beginners, who feel the need to compete all year round. Additionally, don't forget to dress warmly-you'll be out for a while.

| Sample Base Miles Schedule | This schedule is for a typical recreational rider with a full-time career and various obligations. The total training time for the week is 6 to 10 hours depending on strength training and easy day rides. |

| Monday: | Strength training. |

| Tuesday: | Day off or a very easy spin (e.g., 30 to 60 minutes in first gear). |

| Wednesday: | This is an important day. You don't want to neglect aerobic training during the week or else you'll be starting over from scratch every weekend. Try to get in a reasonably brisk ride. This ride will be a little more intense than your base rides but much shorter. Maybe you can work in a 40- to 60-minute ride at lunch time, including a few hills. If you can't get out, a similar ride on the trainer in front of the evening news would be just as good, if not as much fun. Go fairly hard for at least a little while, say two times go five minutes at a time-trial type of effort (i.e., something you could maintain for about one hour). This will provide a maintenance effect that will keep your base work intact from weekend to weekend. |

| Thursday: | Strength training, same as Monday. |

| Friday: | Day off or easy spin. |

| Saturday: | Get out and ride as much as you can, preferably with a group. Groups are particularly good in the winter because you don't want to be out there fighting the wind alone. Try to get in at least two hours or, better yet, three or more. Most of this riding should be easy, as described for Wednesday. Eat heartily after your ride. |

| Sunday: | Continue your base riding, this time try to put in one and a half to two hours. You may feel stiff initially from Saturday's ride, but that's okay. Again, eat heartily after your ride. |

Tireless Legs Part Two: Power

Base

By Jim

Martin

<back to

top>

The movie A League of Their Own includes a scene in which the coach tells a player, "Of course it's hard. Hard makes it good. If it wasn't hard, everyone could do it." That statement sounds great and does a good job of glorifying baseball (and going "hard" in general); it is, however, very misleading. The truth is everyone can go hard. Maybe not today, or tomorrow, but if you take it one step at a time, you can and you will. And when you do, you will find that it is indeed glorious. With that in mind, we will take another step toward achieving the Holy Grail of "tireless legs."

In the last training article (Tireless Legs Part 1), we went into great detail about the hows and whys of putting in base miles. By now, if you followed the advice in that article, you have probably ridden several hundred easy base miles, and with them, you should have the beginnings of metabolic fitness (see "What Is Fitness?" Feb. '97). I'll bet you've found that riding steadily for two or more hours has become progressively easier, and now you're itching for more challenging rides. Well, wait no longer-the time for dialing up the intensity is here.

The next phase is the power base, which will challenge you to ride at a higher intensity so that you recruit both slow- and fast-twitch muscle fibers and start to stress (train) your cardiovascular system. The main physiological effect will be to increase mitochondrial density in your muscle fibers, particularly the fast-twitch fibers and, consequently, raise your lactate threshold. Also, the higher intensity will tend to increase your VO2 max, although specific work targeted to increase VO2 max will come later in the year.

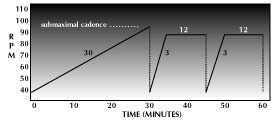

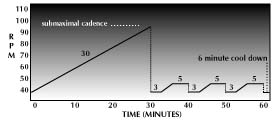

The protocol for power-base riding is very similar to that for base miles. You will want to ride in a group-a line at least three riders long. Two-abreast (echelon) riding is preferred because it incorporates a skill or practice session along with the physiological training aspect. This is particularly beneficial during the power-base phase because you are just beginning to be stressed, and it is important to learn good bike-handling skills under this mild stress before you get thrown into the pressure cooker of your first race or group tour of the season. Be sure to get warmed up with low-intensity riding for 20 to 30 minutes. Choose a route that is long enough so you can spend at least 30 minutes at the front. That is, if the line is three riders long, figure on about 90 minutes for the power-base portion of your ride. Talk with your riding group and decide the length of pulls. For power base, I recommend five-minute pulls, but anything between 3 and 10 minutes will work, and you may want to be flexible depending on the terrain. Remember, when going uphill, the drafting effect is minimal, so a rider who pulls a flat then drafts on a climb is getting a double dose.

Power-base riding differs from base miles mainly in intensity and cadence. The real key to successful power-base training is the intensity of your pull, and you should try to maintain constant intensity throughout your pull. This is the real trick because if you go too hard, you will fatigue before the end of your pull and have trouble staying on when you go to the back. Conversely, if you pull too easy, you will simply not improve your fitness. A heart-rate monitor may help you develop a feel for the right intensity, but keep in mind that these pulls are relatively short and it may take one to three minutes for your heart rate to reach a steady state value which represents the intensity of your pull. Thus, the burden is on you to "feel" the intensity. As a general guideline, the pace you select for your pull should elicit about 90 percent of heart-rate reserve (see "What Is Fitness?") by the time you pull off. Also, you will want to use gears that allow you to keep the pedaling cadence at around 80 to 90 rpm.

The most common error I see is for a rider to go much too hard at the start of the pull and end up blown and off the back. I think the reason people make this mistake is because it is so easy to sit in the draft, you can develop a sort of draft-induced arrogance. You start to think you are much stronger than the wimp in front of you, and when it comes your turn to pull, you take the speed up two or three mph to a more appropriate speed for a stud like yourself. About 30 seconds later, that arrogance meets reality and detonation occurs. A good rule of thumb for avoiding this situation is to hold the same speed as the rider before you, at least for the first 15 to 30 seconds. You may find out that he was not so wimpy after all and that the pace is actually quite brisk. If not, you can take the pace up or down to an appropriate intensity.

Technique: Be Hip!

You have probably heard that the best way to pedal is with a smooth spin at relatively high cadence. In general, that's good advice, but not for power-base training. The key for your power base is to recruit all the muscle fibers, fast and slow twitch. It may seem paradoxical, but the best way to recruit fast-twitch muscle fibers is to stomp on a big gear. By pedaling at a lower cadence, you must produce more force on the pedal (for any given power), and it is the increased force that recruits the fast-twitch fibers. Don't get carried away-I'm only talking about going down to 80 rpm or so. Lower than that may be too much stress on your knees. If you try to grind away at the big gears too soon or without a proper base, you may risk knee injury. Gradually increase the gearing over a period of weeks-after several weeks of base miles-and back off immediately if you have any knee pain.

One side effect of pedaling bigger gears at 80 rpm is that you may find that your quads fatigue. No problem: Don't use 'em. I'm serious-you can pedal without using your quads-just use your gluts and hamstrings to extend your hip. It takes some practice, but if you concentrate you will find that you can relax your quads and just use your hips. It may help to think about aerobics class where the instructor says, "Squeeze, squeeze." You will be amazed at the amount of torque you can generate from your hip with little or no stress in your quads.

So, let's put all the components for power-base riding together:

These simple, but by no means easy, steps will empower you to go harder than you ever thought you could. You'll have to work hard to earn it, but like the coach said, "Hard makes it good." Thanks to all of you who have written. The feedback is much appreciated. Feel free to e-mail me at j.martin@mail.utexas.edu.

| Monday: | Strength training. |

| Tuesday: | Day off or a very easy spin (e.g., 30 to 60 minutes in first gear. |

| Wednesday: | This ride will be similar in structure and intensity to your power-base rides but much shorter. Try to work in a 40- to 60-minute ride, including a few hills. If you can't get out, a similar ride on a trainer would be just as good. Simulate a few power-base pulls by doing 3 to 10 minutes of higher intensity with approximately 5-minute recovery periods. Do a total of at least 20 minutes of higher-intensity effort during the ride. Think about technique-pedal from the hip. This will provide a maintenance effect that will keep your power base intact from weekend to weekend. If you have the opportunity to ride with a group or even one other rider, take advantage of it. |

| Thursday: | Strength training, same as Monday. |

| Friday: | Day off or easy spin. |

| Saturday: | Time for power-base rides as described in the article. Try to get in at least two hours, with at least 30 to 60 minutes spent pulling. Again, think about technique and pedal from the hip. Eat heartily after your ride. |

| Sunday: | Continue your power-base riding. This time try to put in one and a half to two hours, with about 30 to 40 minutes of pulling. Work on technique-pedal from the hip. If you find that you're not recovered from Saturday's ride, just sit at the back and either work in every other pull or treat it as a base ride. |

| * This schedule is for a typical recreational rider during the power-base phase. It consists of three days of cycling training, two days of strength training and two days off or recovery rides. The total training time is 6 to 10 hours, depending on strength training and easy day rides. | |

Training for The

Pack

By Jim Martin

<back to

top>

So you have aspirations to ride in the bunch, huh? Understand this: The peloton accelerates faster than a World Cup sprint, corners like a pro criterium field, climbs as if contesting King of the Mountain points and hammers the crosswinds relentlessly. In other sports, each person may have strengths and weaknesses that allow him to gain or lose ground at various points of his event. But in cycling, one moment of weakness in any of the various disciplines will send you flailing off the back, never to be seen again. This challenge is what makes cycling such an attractive sport: To do well, you have to have it all. This month, we will describe a few situations you are likely to see on a pack ride and provide methods to train for them before you get thrown into the vortex of the peloton.

If you have been following our training articles over the last few months, you will have the fitness to perform the workouts described in this article. However, if you have not laid a proper base with a progression from relatively easy to relatively intense riding, these workouts will be much too intense and you will simply not be able to do them. I'm not trying to scare you off, but this is crunch time; the peloton takes no prisoners and accepts no weakness.

Pack riding is a totally different animal than solo cycling or even rides with several friends. There are a few anomalies to be aware of. Whether it's your first race, club ride, sport tour, charity ride or even your first time racing in a new category, the first thing you are likely to experience is speed shock, from the insanely fast speed the peloton adopts from the gun. Within a few seconds, you will find yourself sprinting with everything you've got just to stay in the group. Your mind will be telling you that this behavior is insane and that you must ease up and pace yourself. Don't! Everyone else in the group is human just like you, and they can't go all out for too long. Consider speed shock your welcome into the bunch.

During climbs, the whole sport of cycling changes. As soon as the road points up, you find yourself in a weight-bearing sport with little or no help to be gained from drafting. Unless the climb is really long, you'll be climbing above your VO2 maximum power, that is, some of the power will come from anaerobic metabolism. Thus, the fitness required for climbing is similar to what is required for handling attacks, except for one thing: pedaling cadence. Most riders climb at a much lower pedaling rate (revolutions per minute, or rpm) than they ride the flats. The lower rpm requires higher torque (more force on the pedals) to generate the same power and, consequently, climbing produces somewhat unique demands.

The intense speed of the attacks and climbs in the peloton, combined with the high average speed, demand that you integrate all your physiological systems: aerobic power, anaerobic power and anaerobic capacity. Until now, our on-the-bike training has focused on aerobic power, and our off-the-bike strength training has been designed to lay the base for anaerobic power.

Here is the workout that will bring all the components together for you: sprinting time-trial intervals. Sounds great, huh? The best way to perform these is to find a loop about 12 mile in length with a short, steep climb. The climb should be about 30 seconds long at your absolute all-out sprinting power. You will use the climb to elicit a huge oxygen deficit which will take you right to the edge of complete fatigue. The real key to these workouts is the work you do after the climb. As soon as you crest the climb, settle right into a hard time-trial effort. This is the essential element that will build your capacity to handle the sprint-recover-sprint-recover nature of riding in the peloton.

Six Hard Steps to Fitness:

Start at the top of the climb and begin riding your loop at a hard time-trial pace. Maintain that pace until you reach the base of the climb (about one minute).

At the base of the climb, pretend you are nearing the end of your interval and sprint all out for the top. In your first session of these intervals, you may want to keep the sprint short, say, 15 seconds, and increase to 30 seconds over two or three sessions.

Now here's the gut check. When you get to the top and you're totally gassed from your sprint, settle back into the best time-trial effort you can muster. It may only be 12 to 18 mph, but it has to be time-trial effort. Suck it up and go hard!

Take advantage of the loop to work the corners. Gradually try to increase your cornering speed. Force your eyes to look past the apex, and leave your braking for later into the turn.

Keep this routine up for six minutes.

Repeat this four times with a 10-minute recovery.

If you can't find a loop like I've described, you can do these exercises on any road, but the key is that you must sprint all out for about 30 seconds out of every minute and a half you ride. So on the road you could do these by beginning with a one-minute time-trial effort followed by a hard 30-second sprint, then settle back into a hard time-trial effort and repeat for a total of six minutes. Of course, by not using a loop with a hill, you may not get the climbing or cornering practice, so look around. I'll bet there's a nice loop within 20 blocks of your house.

This workout is very demanding and you may have a hard time staying motivated for a whole interval session, so bring a partner. If you and your partner are well matched, you can ride side by side or, even better, in a single-file paceline for the time-trial part and side by side for the climb. If you are somewhat mismatched, you may want to handicap the start so that the stronger rider must go all out to catch the first rider by the end of the six minutes.

These exercises are very stressful and demand that you take care to ensure proper recovery. The nature of high-intensity anaerobic work is that it burns stored muscle glycogen at rates that are up to 15 times higher than aerobic work and generates high levels of metabolic by-products, including oxidative free radicals. Because of the relatively inefficient nature of anaerobic metabolism, you can end up very nearly glycogen depleted in a very short time, and you must replace that muscle glycogen before you can expect to perform again at high intensity. Therefore, you should consider proper nutrition an important part of your training. Down one of your favorite sports drinks (a specifically formulated post-workout recovery drink is best-Ed.) and an energy bar upon finishing the workout and follow that with a regular, high-carb meal-you'll speed your recovery tremendously.

Anaerobic work generates oxidative free radicals that can be very damaging to muscle tissue. Antioxidants (more properly termed free-radical scavengers) combat these free radicals and prevent the damage they can cause. In general, studies have shown that muscles treated with antioxidants such as vitamins C and E and beta-carotene recover more quickly and to a greater extent. Therefore, during periods of heavy anaerobic training, you should consider adding foods or supplements to your diet that are high in vitamins C and E and beta-carotene.

Along with the need to replace muscle glycogen and protect against oxidative free radicals, recovery rides become more important during periods of high-intensity training. Rides of 40 minutes to an hour and a half performed at very low intensity can speed recovery from these training sessions in two ways: The increased blood flow to the legs help flush various metabolic by-products out of the muscle tissue, and even an easy ride increases the muscles' ability to take up blood glucose and thus facilitates the replacement of muscle glycogen.

Group rides are the most exhilarating aspect of cycling, but getting dropped

is easily the most depressing. By performing high-intensity training as

described, you will have a much better chance to stay in the bunch and

experience the

excitement.

Building

the Perfect Cyclist

By

Jim Martin

<back to

top>

Strength and

Power.....

Strength and

Power.....

How to Be a Monster on the Bike

Ask Frederic Guesdon how important raw power

is to a cyclist and he'll tell you all about his 1997 Paris-Roubaix win. The

little-known rider for team Les Francaises des Jeux surprised his star breakaway

mates with a ferocious sprint he uncorked at the finish on turn three of the

Roubaix velodrome, using a mere 100 meters to shoot from the back of an

eight-man group and win by a comfortable four bike lengths. How did the young

second-year pro Guesdon go from zero to hero at the expense of some of the

world's best riders? With power to spare. Here's how to win your own town-line

sprint or just drop a persistent wheel-sucker.

"What we're trying to accomplish is power gains on the bike," former pro triathlete Ray Browning said. With a master's degree in exercise physiology and biomechanics, Browning is the Biomechanics Laboratory Coordinator for the Boulder Center for Sports Medicine, a nationally renowned exercise physiology center. "Ideally, we want the ability to convert strength into raw power for short bursts of energy," he said. "When you think about it, the power phase of a pedal stroke¬the leg extension on the downstroke¬only lasts two-tenths of a second or so. That's where your power comes from."

Strength training is a year-long process that should actually start at the end of a season. "The first step is to identify your strengths and weaknesses," he said. "Are you a weak climber or sprinter? Have you had any injuries last season that held you back? A really helpful idea is to schedule an evaluation with a physical therapist, then create a winter strength program."

That means mostly gym work during the off-season, Browning said. The first phase is general strength building, with an emphasis on muscle balance, and should coincide with your base-miles training on the bike, during a two-month block from late January through March. "I'm a big proponent of strengthening your lower back and abdominals¬your core," he said. "I like general exercises like the bench press, shoulder raises and seated rowing for upper body work. Seated rowing is especially good for cyclists. Combine three or four upper-body exercises with leg work¬like squats, leg presses and curls and calf raises¬and add in floor work, crunches and leg lifts and you've got a good circuit of eight or nine exercises." See the strength schedule in the training charts for specifics.

Do two to three sets with 10 to 15 repetitions each. The 10th to 15th reps should "be difficult, but not impossible," Browning said. For those who don't enjoy their time in the gym, take heart. "You can do this circuit in about 45 minutes, and for cyclists (who aren't interested in building much bulk) you only need to do it two or three times a week times, maximum," Browning continued. If you can't make it to a gym, there are alternatives. "Be creative. I did a strength program in my own house one winter with a couple of sandbags, a chair and a pull-up bar," he said.

As you introduce variety and intensity into your training, it's time for what Browning calls his maximum strength-development phase. "It's about a one-month period where you'll convert all that strength into power on the bike," he said. These circuits will include only our four lower-body exercises and just one for the upper body...seated rowing. "Increase your sets to between four and six, while decreasing reps to six or under," he said. "The weight should be about 90 to 95 percent of your maximum lift."

One way to help increase power is to lift more explosively during this phase. Continue to use good form, though, and don't snap your joint at the apex of the lift. "You can also incorporate plyometrics at this point," he said. "A really good resource for this is Jumping Into

Plyometrics by Donald Chu ($13.95, Human Kinetics Publishing, 800/747-4457; www.humankinetics.com). You can also start strength work on the bike. Solo exercises include hill repeats--climbing a hill in a larger gear--or sprint intervals (which can also be done with a group).

"What you want to do is gradually shift your emphasis to on-the-bike work as the season approaches," Browning said. "During the summer it's advantageous to continue strength work, but it's more for maintenance then; you're not actually trying to increase strength. There's been research to suggest that power dropped off in athletes who discontinued strength work during the season, so now's a good time to go back to your original strength sessions. The focus during the season is recovery, so your strength workouts shouldn't leave you sore."

A good strength and power program will make you both a stronger cyclist and one less prone to injury. The best time to start a strength program is at the end of a season by using Browning's advice about evaluating yourself. But even in June, starting a light circuit workout will show dividends in only a month. Use that to springboard you into next season¬your strongest yet.

...Strength and Power from the Neck Up

One of the beauties of cycling is the merging of mechanical technology with physical prowess. By designing a gear-driven two-wheeled machine, humankind was introduced to a device so efficient that even a person who lacked fitness could travel short distances without exhaustion. In fact, the bicycle remains the most efficient human-propelled vehicle ever invented. While cycling enthusiasts frequently converse about sculpted athletic bodies and finely wrought frames, it's much rarer to hear talk of a certain cyclist's mind; in truth, it should probably be the other way around.

After all, many riders have shared the experience of meeting a visitor on a club ride who appeared out of shape and rode a cobweb covered bike he had just discovered in the attic of his grandparents house but who, nonetheless, handily dropped everybody on $1500 bikes up the first climb. In such cases, mental toughness proves to be the common denominator. Most who have been with the sport a while recall certain instances of determination that sent chills along their spine, such as LeMond clawing his way back to the top of the sport after nearly dying in a hunting accident. Those fortunate enough to have observed LeMond take 58 seconds out of Laurent Fignon in the final time trial of the '89 Tour de France well know that, regardless of fitness and aerodynamic considerations, LeMond's legendary ride--which continues to stand as the Tour's fastest time trial--was the result of sheer determination. Discovering such mental toughness in ourselves, however, can often be a difficult matter. Fortunately, unlike VO2 uptake, there appears to be no limit on developing the mind to adjust to hard efforts.

According to Toby Stanton, a coach for Hot Tubes Racing (formerly G.S. Mengoni) with 19 national championships to his coaching credit, mental toughness can be developed in much the same manner that a person improves his or her fitness. "Encouragement is one of the best ways to develop toughness," Stanton said. "Also, being surrounded by other good riders tends to help a person develop toughness. Many times I've seen a new rider arrive on my team, who seemed a little shy at first, but after racing alongside team members who were doing well, soon became aggressive and tough in his own right."

While such a stance dispels any myths about mental toughness being a genetic quality, Stanton did note that some sports, such as hockey, seem to draw a more toughened group of competitors than cycling or cross-country skiing. Stanton doesn't deny that cycling and cross-country skiing can be brutal sports. "Both require a great level of endurance," he continued. "Endurance, though, is the easiest component of training to build. Short bursts at maximum effort are the most difficult and, as a result, require a much tougher mind. It's during these efforts that races are won." To judge personal mental toughness, Stanton suggests putting on a heart-rate monitor and attempting to reach 180 beats per minute and holding it while cranking down a gently sloping descent: "After all, anyone can push their heart rate up on a climb, but how many can push themselves on the flats or even a downhill? That's mental toughness."

If you can't afford such luxuries as a heart-rate monitor and live in a region where there are few others to ride with, setting small goals is one way to harden your mind for maximum efforts. One method is to locate a series of telephone poles or other landmarks, such as mile markers, that are spaced anywhere from a few hundred meters to a full mile apart. Once you've located suitable markers, go all out between the two markers, starting at full effort and attempting to hold it until you reach the following marker. If you do have others to ride with, set a goal such as staying with a stronger rider up the first section of a local climb. As you continue developing, set a slightly more difficult goal. In the process, you'll find yourself adjusting to tougher situations.

Setting too difficult a goal, however, nearly always results in failure. As Stanton pointed out, "A junior rider would be much wiser to attempt placing high in a junior race, instead of entering a senior race with the goal of simply finishing." Developing the mind-set of a winner is a delicate process. Many people are able to finish high, often within yards of the winner, yet victory always eludes them. Attending a small local race and winning develops the psychology of a winner, instead of going to a national-caliber race and getting dropped three laps into the event.

Recreational riding, in turn, can be equally difficult. Going out and riding four days a week for 45 minutes at a time is wiser than immediately planning out a schedule that calls for riding an hour every day of the week. For those rare individuals who are born with a tough mind, almost any task appears easy to accomplish. But for the rest of us who must work hard to accomplish similar goals, the key is to first find enjoyment in riding and then, later, push yourself. Once you've developed a healthy schedule of enjoyable days balanced with more difficult days on the bike, you will find your fitness blossoming along with your confidence.

| Resources

One of the most thorough books on mental preparation is Marc Evans' Endurance Athlete's Edge (Human Kinetics, P.O. Box 5076, Champaign, IL 61825; 800/747-7757; $19.95). Evans focuses on many diversified aspects of mental preparation, such as goal setting, imagery training, mental fatigue versus physical fatigue, negative thoughts and positive self-talk. While his primary training is as a coach for triathletes, his methods transcend sports categories. Renowned cycling physiologist Ed Burke also addresses mental issues in the recently reissued Cycling Health and Physiology (Vitesse Press, 4431 Lehigh Rd., #228, College Park, MD 20740; 310/772-5915; $17.95). Finally, those interested in getting information straight from the horse's mouth should consult Greg LeMond's Complete Book of Bicycling, available at your local bookstore. While LeMond's book doesn't focus solely on mental development, it makes for fascinating reading. |

How Long Can You

Last?

Typically, the best way to train your muscles to fire for

long periods of time is to put in what coaches tend to refer to as "base

mileage." These miles should be steady and easy and applied as liberally as

ketchup to a french fry. The low intensity of solid base miles prepares your

muscles for the repetitive nature of the longer endurance ride. Ride duration is

increased slowly and for most riders shouldn't be increased by more than 10

percent at a time once you're riding 50 miles a week.

Team Hot Tubes' Toby Stanton will tell you that you needn't be able to ride 50 miles in order to be able to race 50 miles. Huh? "If you go out to ride 100 miles, it's going to take you seven or eight hours," Stanton says. "But if you race that distance, it will take you five hours or less. Your body doesn't understand miles, but it understands time." So Stanton coaches his riders to concentrate on training the length of time it will take them to race a given distance.

What that means for you is that if you are preparing for some sort of longer group ride, you only need to train toward the amount of time it will take you to complete the ride, not the distance. If your weekend group is going to do a metric century one Sunday and the group typically averages 20 mph, then all you need to be able to ride is three hours. If you work toward that duration gradually, then your last training ride prior to the metric century need only be about 2 hours and 45 minutes long.

Mike Niederpruem, manager of coaching programs for USA Cycling, concurs. "You don't have to be able to do a metric century in order to be able to do a metric century," Niederpruem states. "The conventional wisdom is to get base mileage." But he says there is now substantial research showing that endurance adaptation takes place even when training for short, intense events. Niederpruem advises that time-crunched athletes need not give up the goal of completing a century. While he grants that the best route to endurance will always come from logging the miles, he says endurance can be gained from doing longer interval work. "Intensity can help make up for the lack of time," Niederpruem explains.

Just because you've done the training necessary to endure the event doesn't mean you can suddenly ride above your ability. Says Stanton, "They gotta be sitting in, not driving it. They gotta be smart." Being smart means keeping your nose out of the wind as much as possible. "You gotta understand you get a huge advantage by riding in a group when you do an event," he says.

According to Stanton, one of the toughest lessons you must learn in order to establish endurance is eating on the bike. "You gotta eat when you're not hungry," Stanton says. "If you bonk, you're never gonna restart; you might finish but you won't ever get going again." Because most of us are accustomed to riding shorter distances we haven't had to train ourselves to eat much on the bike, but when preparing for a longer event it is important to begin eating earlier in the ride and continue to eat frequently. Most coaches advocate eating something every half hour and drinking a bottle of water an hour, unless conditions are really hot, in which case you should drink even more.

The final ingredient to making sure your legs last the day is to make sure the rest of your body is happy. You may need to pick up a pair of gloves if you don't ordinarily ride with them so that your hands won't get sore. Consider purchasing a really nice pair of shorts if you are prone to soreness in your butt; saddle sores, a more extreme phenomenon, can prematurely end your fun.

You'll know when you've found that holy grail of endurance. The feeling that you could ride all day is unmistakable. For many of us, it is that very feeling of freedom that attracted us to road riding in the first place.

| Indoor Options If you want to prepare for a longer event but lack either time or daylight, there's no need to think you're completely hosed. With the aid of an indoor trainer or indoor cycling class you can perform intensity training to help you sustain the longer effort necessary for the big day. If you prefer group activity, then you might want to try an indoor cycling class. Typically held in health clubs, these classes mix high-intensity training with high rpm by varying the resistance on the flywheel. There are other health clubs offering similar classes that use ordinary stationary bikes in an interval-format class. The idea is to train hard enough to reach your lactate threshold, stay there for a period of time, then recover so you can do it again. The physiological adaptation that will allow you to ride longer distances will come from your super-hard efforts. If you just climb on an indoor trainer and ride hard for an hour, you won't make any progress. However, if you pedal through a set of six three-minute intervals and recover, your body will become stronger. It won't be the most fun you've had, but no one said intervals were a party. The great advantage of going to an indoor cycling class is the group camaraderie fostered by the instructor. You'll find yourself working harder than you thought possible. The workout, shoehorned into less than an hour, will leave you a breathless, sweaty mess¬exactly what you need if time isn't on your side. |

Balancing Your Fitness Program

When increasing your mileage base, you can physically watch your muscles take shape, slowly toning themselves into smooth curves until finally becoming distinctly cut: sharp lines along the lower edge of your calves, the double ridge of the quadriceps folding neatly into the knee joint. Stretching, on the other hand, presents no immediately visible results; your muscles look much the same. Improving range of motion is, more often than not, slow going. Furthermore, unlike dedicated riding, stretching burns few calories. So why, you might ask, should I spend my time increasing my flexibility?

Concentrating your efforts into a stretching program improves your life twofold. Physically, it reduces injury, back pain and muscle soreness while improving posture, recovery and muscle coordination. Mentally, stretching is one of the oldest meditative practices known to humankind. While stretching, you are able to not only relieve the tension of each muscle, you can also reduce anxiety, by contemplating and resolving situations from racing strategies to relationship problems. Many cyclists use their bike as a tool to help relieve tension accumulated at the office or home. Going on a long ride provides solitude, even when riding with others. During an hour-long ride, our mind often travels farther than our bike. The only downside of riding is that rather than reducing tension, we actually increase it through tight, sore muscles and, occasionally, when we push it too hard, a tired, sluggish mind. While the benefits of stretching aren't as apparent to others as purchasing a new sweater or losing 10 pounds, you'll quickly notice how much more relaxed you are at home, in the office and, of course, on the bike.

Stretching should only be attempted after warming up, whether 10 minutes into a ride or upon returning home afterward. Increasing body temperature allows for greater elasticity of the muscles and connective tissues. If you prefer stretching in your living room, jumping jacks and running in place for a few minutes are adequate warm-up. Stretching cold, unfortunately, has no benefit and can actually increase the chances of injury by stretching too far and pulling a muscle. Cyclists will naturally want to concentrate on their legs (calves, hamstrings and quadriceps), lower back and neck muscles to increase riding comfort. Lengthening your hamstrings through daily stretching will eventually allow you to increase your saddle height by a centimeter (and in rare cases two centimeters) which gives you the distinct benefit of greater power as a result of increased leverage.

During extreme efforts, blood swells the quadriceps, leaving traces of lactic acid when the effort is finished. The more supple the muscle, the greater the blood flow, allowing for faster recovery while riding. By increasing blood flow, lactic acid that would otherwise remain in the muscle (creating soreness the following day) is quickly washed away. Not only does stretching increase recovery both on and off the bike, it also reduces the chance of overuse and trauma injuries.

Through stretching you can increase the flow of synovial fluid, which lubricates joints and transports nutrients to articular cartilage, greatly reducing overuse injuries, especially in the knee. By the same token, trauma injuries caused by high-speed crashes are also reduced. Muscles that might otherwise tear in a crash are able to stretch beyond their original range of motion when limber.

While high-speed crashes may be an unlikely event for many riders, sore neck and back muscles are commonplace with both professional racers and weekend warriors¬even desk jockeys fight with cramped necks and backs. Tight neck muscles can be relaxed by tilting the head and holding it for 15 seconds. Working the kinks out of your back requires a little more space, but as with all stretches you'll want to stretch the muscle just shy of the point where you feel pain and hold it for approximately 15 seconds. While working through a routine, you can begin to explore the mental possibilities of stretching.

Cynics who find the physical benefits of stretching uncertain will find the possibility of mental gains even more nebulous. This is one area of fitness where the pragmatic mind must submit to the intuitive. Incorporating stretching with mental calisthenics requires no special training. The method is quite simple: While stretching, concentrate on breathing, first steadying your breath, then focusing on exhaling. As you stretch, release the tension of each muscle with each exhalation. Your breathing pattern should be slow and even, drawing air deep into your diaphragm. Don't consciously force air out of your lungs¬simply focus on the spent oxygen leaving your body. As the exhausted fuel exits your lungs, allow muscle tension to travel with it.

As you work through the different muscle groups, you will find your body falling into a deeper state of relaxation. Over two or three months you'll notice your posture improve as each muscle group becomes balanced alongside the others. Once you have developed a comfortable stretching routine, and learned how to steady your breathing patterns in conjunction with stretching, you can begin to explore other possibilities, slowly transforming stretching into a meditation session. By now, releasing tension with each exhalation will have become second nature, allowing you to move into other areas such as visualizing a victory or coming to terms with problems in your personal life.

Attaining true fitness requires a multidimensional commitment. Cycling is only a single component to a healthier lifestyle. Stretching, in turn, can help round out your fitness plan, but only as a means to an end. Learning how to synthesize stretching and meditation may be the missing part of the whole.

Nutrition....

Nutrition....

Fuel for Perfect

Fitness

As a cyclist, your dietetic needs don't vary much from the

rest of the population. The guidelines established in the USRDA will work well

unless you are training more than 10 hours in a week, in which case all you

really need to do is raise the number of calories you are taking in on a daily

basis.

The food pyramid is as applicable to cyclists now as ever before. Fad diets have virtually no clinical support, while all clinical studies involving athletes continue to show the benefits of a well-rounded diet in their development regardless of the discipline. Muscle adaptation is quicker, as is recovery from a hard effort. Cravings for evils such as bear claws also seem to wane (well, at least sometimes the pull is not so great).

Breads, Cereals, Rice and Pastas

Since this group forms the base of the pyramid and provides a rider with most of the carbohydrate he needs to perform, it's important to try to get in the daily recommendation of six to eleven servings per day. Whole grains are recommended as are foods that are low in fat and sugar. The more diverse the sources of your grains, the healthier your diet will be. Spreading your intake of these carbohydrates throughout the day will also prevent huge swings in your blood sugar which can help stabilize moods.

Vegetables

Since different vegetables provide different nutrients, a diet rich in a variety of vegetables will prevent the need for vitamin supplements. The recommendation is for three to five servings daily¬far more than most of us get, especially if you have a hostile relationship with one or more of those veggies that your mom made you eat. Dark green, leafy vegetables and legumes are particularly good sources for many vitamins and minerals that cyclists need. Many legumes, when combined with rice, will provide a complete protein (one that has all the necessary amino acid chains); it's possible to be a vegetarian and still build muscle.

Fruits

Satisfying the recommendation for two to four servings of fruits is pretty easy to do, especially if you like to rehydrate on 100 percent juices. Punches and 'ades don't count (at least not fully). If you are looking for additional ways to work more fiber into your diet, then eat fruits instead of drinking them. While you can satisfy your intake with fruits that are dried or canned in syrup, nothing beats fresh fruit.

Meats, Poultry and Fish

Most American diets include twice the recommended daily allowance for protein, which comes primarily from the intake of meats, poultry and fish. This means that the two to three servings daily recommendation is actually more like four to six for most of us. The good news is that most active cyclists do need more protein than the daily recommendation, so you probably won't need to alter your intake in order to ride happily. When shopping for meat, poultry or fish be sure to choose lean cuts and trim any excess fat before cooking. With poultry, remove the skin as well. When preparing a dish remember that broiling, roasting or steaming these foods will contribute much less fat to your diet than frying them. Many nuts and seeds can also provide protein (as can legumes), but most nuts and seeds are high in fat and should be consumed in moderation. However, the polyunsaturated fat in nuts and lighter oils (like olive) is much better for you than that slab of bacon.

Milk, Yogurt and Cheeses

Don't get too excited, a pint of Ben and Jerry's Chubby Hubby is not recommended. While two to three servings of milk products are recommended daily, this is a territory that can easily get you into trouble. Most cheeses and yogurts are available in low-fat versions just like milk. By sticking with skim or part skim milk products you can cut your intake of dairy fat in two. As with meat, most Americans exceed the recommended number of servings.

Fats, Oils, and Sweets

The watchword with this group is "sparing." Not like "Spare the rod and spoil the child," rather "Use these things sparingly." When eating breads avoid putting butter or margarine on them. When adding a dressing to a salad do so lightly and try to use a low-fat dressing¬a vinaigrette as opposed to a creamy ranch (or a creamy anything for that matter). Avoid cooking with sugar (maybe you can add a bit to those oatmeal cookies); instead try using fruit juices or applesauce.

That takes care of what to do while you are off the bike, but you do need to give some thought to the foods you consume on the bike that aren't sold in a mylar wrapper. This is especially important if you are planning to ride a longer event like a century.

If you have a fussy stomach, you'll want to do your experimenting with foods before the big day. If your plans include an organized ride with rest stops stocked with food, try calling the promoter to find out what they'll serve. If they only plan to have vanilla creme sandwich cookies, you might want to try packing a jersey full of them to see if you can survive on cookies for two hours. If not, bring your own food along. Drink mixes can have widely varying effects depending on how strongly they are mixed. If you find out the Gatorade is being mixed a little thinner than you usually drink yours, you'll need to drink or eat more in order to make sure you are taking in enough calories¬after all, eating intelligently means not only eating the right foods, but eating them in the right amounts.

Recovery...

Recovery...

Be Your Own

Soigneur

"I get a lot of people saying to me, 'I'm training really

hard, but I'm just not getting any better,'" Cycle-Ops' director of training

programs Chris Carmichael said during a recent interview. "Their training is

fine, it's the recovery part that they're not doing right," he continued.

Carmichael, USA Cycling's former national coaching director and the architect of

America's most successful Olympic showing since 1984 (Atlanta '96) knows a lot

about recovery. A former elite racer himself and coach of some of today's top

pros, such as Lance Armstrong and Bobby Julich, Carmichael has had ample

opportunity to refine his views on what he considers the most underrated aspect

of cycling.

"What's most important about recovery is that riders understand what the process is," he said, "...the actual stage where you adapt and get stronger; training is just the stress phase¬recovery is where the real gains are made." Recovery is also a lot more than just sitting on the couch. It's cooling down, eating right and basically paying attention to your body's needs following a hard workout. Pros have trained soigneurs to do all this for them. You have, well, you. Here's how to be your own soigneur and pamper yourself post-ride.

Late in the Ride

"Cooldowns aren't nearly as actively practiced as warm-ups," Carmichael said. "But warming down, just putting it in a lower gear and spinning easily for the last 15 minutes of the ride, helps the blood continue to move acid buffers in and sweep waste products out." If you just hop off the bike with your heart racing, your body starts to shut down from your hard efforts, decreasing your circulation and leaving those waste products to build up and inhibit recovery. If you're on a group ride that finishes with a town-line sprint, take a short spin before relaxing over coffee with your riding buds. Not only will they understand, but you might just start a new post-ride routine for your group. As you're warming down, drink the rest of your water and even pop a gel if you have one handy.

Food, Part One

"Right after your workout is a crucial time for your body," Carmichael said. "You're glyco-depleted and you need food right away. I can't emphasize enough the importance of the glycogen window." That's about a one- or two-hour period when your body is especially receptive to reloading blood and muscle glycogen stores. Miss it, and you'll be hurtin' for certain the next day. Carmichael said that it's hard to eat too much food following a good hard ride, but you have to eat the right kinds. "Have a carbo drink first thing," he said. "You're trying to replenish blood sugar levels first, so that means simple sugars. Then have an energy bar and follow that up with a post-ride recovery drink."

Intermission

After slugging down some immediate picker-uppers, put on some water for pasta. As it's heating, work some of the kinks out of your muscles with massage and stretching. "Massage helps improve recovery by working out all those little knots in your muscles that cause spasms and constrict circulation," Carmichael explained. A combination of stretches and kneading will relax your tired limbs and make your body more receptive to healing. Check out Roger Poleznik's book Massage for Cyclists ($14.95, Vitesse Press, 301/772-5915) for do-it-yourself hints, or go to the American Massage Therapy Organization's web site at www.amtamassage.org for a list of certified local therapists.

Food, Part Two

Next, get the complex carbs and protein your muscles need. A good meal of pasta, vegetables and a protein source will top off your muscle stores and give your body the fuel it needs to start repairing the damage wrought during your workout. Don't forget to drink plenty, too. "I see lots of chronic dehydration, where riders aren't rehydrating to 100 percent," Carmichael said. "They get 98 percent there and start the next day a quart low. Over time, that catches up to you." So stuff your face, tip back a glass or two. Just stay away from alcohol and caffeine, no matter how good a hefeweizen or iced cappuccino might taste. Both are diuretics and will do more harm than good for your recovery efforts.

Nap Time

"I think that if you called any European-based pro at three in the afternoon, you'd catch 'em napping," laughed Carmichael. Rest is an important component of recovery, and when it comes down to it, nothing beats a nice afternoon snooze. Now that you're stretched out, refueled and rehydrated, catch up on your sleep. But after your nap, there's one last thing¬more riding!

That evening, hop on the wind trainer or rollers. A brief 15-minute spin at low rpm and gears can help facilitate blood flow and recovery, working the stiffness out of your muscles almost before it sets in. While you may not be motivated for even a quarter-hour roller stint, doing so will help you get faster with less stress and pain.

The Next Day

After all that pampering, you might feel rarin' to go next morning. Don't. All that hard work after yesterday's ride could be wiped out if you go out hard. "The number one error I see in people's routines is they don't leave enough time between hard workouts," Carmichael said. "I only schedule three hard workouts back to back for my guys, and they're the elite of the elite. For most people I'd say don't go more than two hard workouts without recovery work, and novices should definitely alternate hard and easy days." Take an easy spin and think low: low gear, low heart rate (under 70 percent of max, Carmichael recommends) and low rpm. Fast spinning can be harmful because it requires lots of muscular control, and that's stressful to your legs. So spin easy at under 90 rpm, and watch the scenery rather than your stem. Tomorrow you'll be ready to rip.

Illustrations by Bill Cass

To build overall strength and fitness for cycling, and specifically to produce more power on the bike, you'll need to use strength training. Here's a year-long program in four stages that coincide with the riding season to help improve your power.

Strength Training

Winter and Early

Spring (January to March)

Bike work: Base

miles

Strength work:

About 45 minutes, one to two days a week in the gym. Circuit workout with leg